1965

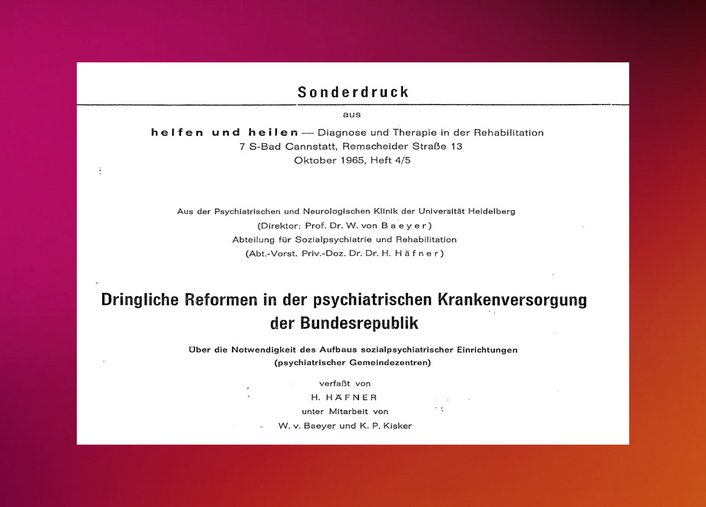

Häfner and colleagues publish a memorandum

Together with von Baeyer and Kisker, Häfner publishes the memorandum Urgent reforms in psychiatric care in the Federal Republic of Germany. He reports the following facts and figures on the current situation, which he describes as a “national emergency”:

- Mental illnesses are not incurable, but can be improved or cured to a relatively high degree with the appropriate methods. This was not common knowledge in 1965.

- Around 10 percent of all mentally ill people require inpatient treatment. Around 50 percent can be treated on an outpatient basis and the remaining 40 percent could be treated by general practitioners if they were suitably qualified.

- There are only 92,000 beds available for around 550,000 sick people in Germany, of which only around 1,500 to 2,000 are at university hospitals.

- The state psychiatric hospitals are too large and predominantly geared towards detention.

- In the state hospitals, one doctor is currently responsible for 100 to 200 patients. In contrast, the German Council of Science and Humanities recommends one doctor for every 15 patients in psychiatric hospitals and one doctor for every 10 patients in university hospitals.

- The USA has 450 beds per 100,000 inhabitants, Germany has 176.

- The staffing situation in hospitals is characterized by a major shortage of personnel and training. This is due to the cuts in the period from 1933 to 1945 and the current unattractiveness of psychiatric care as a field of work. In 1965, there were only around 30 clinical psychologists and around 40 psychiatric social workers in the whole of Germany.

- In Germany, “a large number of sick people are kept in families for years without treatment or with inadequate general medical care (...) until their suffering becomes chronic and their ability to work or earn a living can no longer be restored”.

- The total economic costs of mental illness (direct and indirect costs) probably account for the largest share of total expenditure on illness and its consequences in Western countries.

The authors' central demands are:

- The establishment of social psychiatric community centers with the following areas: inpatient department, day, half-day, night and weekend clinics, outpatient department and diagnostics, pre- and after-care facilities, rehabilitation service, psycho-hygienic department (for general education and external specialist advice), geriatric department and adolescent department (to offer adolescents and young adults a suitable therapeutic community that they cannot find in either child or adult psychiatry).

- A psychiatric hospital must be located in larger residential or industrial areas.

- In order to provide optimal psychiatric and psychotherapeutic care, Germany needs around 250 new community centers, each with around 200 inpatient places, as well as outpatient treatment and care options for 600 to 800 people.

- Registered psychiatrists should work part-time in the community centers in order to increase their treatment and training capacities

The number of new therapeutic specialists of all professions must be increased considerably.

According to Häfner, in order to shape the change, an institution is needed that can provide “model organizational forms, experience and a core of trained teaching staff and specialist personnel for the expansion of the numerous centers to be planned.” The greater Mannheim-Heidelberg area is particularly suitable for this, as it is diverse in terms of population and therefore representative, offers good rehabilitation opportunities and because the core of such a center already exists with its Department of Social Psychiatry and Rehabilitation and its cooperation partners. Häfner then outlined the structure and required capacities of the model facility in detail.

Despite the well-founded argumentation, the memorandum initially had no direct impact on health policy in Germany.

Zentralinstitut für Seelische Gesundheit (ZI) - https://www.zi-mannheim.de